Cryptocurrency, but secure

The Heinz Nixdorf Foundation supports Clara Schneidewind's research group with 1.15 million euros

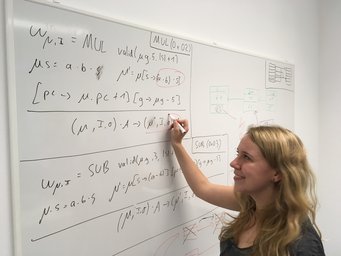

Making blockchain technology and thus cryptocurrencies more secure and improving data protection in transactions with this new means of payment. These are two of the goals that Clara Schneidewind is pursuing with the Heinz Nixdorf Research Group for Cryptocurrencies and Smart Contracts at the Max Planck Institute for Security and Privacy. The Heinz Nixdorf Foundation has been funding the group since September 2021 with 1.15 million euros for the next five years.

Blockchain technology is like almost every other new invention: it brings new opportunities, but also bears some risks. With a blockchain, transactions that require a lot of trust, such as payment transactions or the conclusion of contracts, can be processed transparently and decentralized. An account, for example, is no longer managed centrally by a bank, but distributed across many computers worldwide: they all store the necessary data so that everyone can see who owns what amount of a cryptocurrency. What has arisen from a certain distrust of established institutions, however, comes with new requirements for data security and data protection.

Protecting blockchain software is particularly difficult, and particularly important

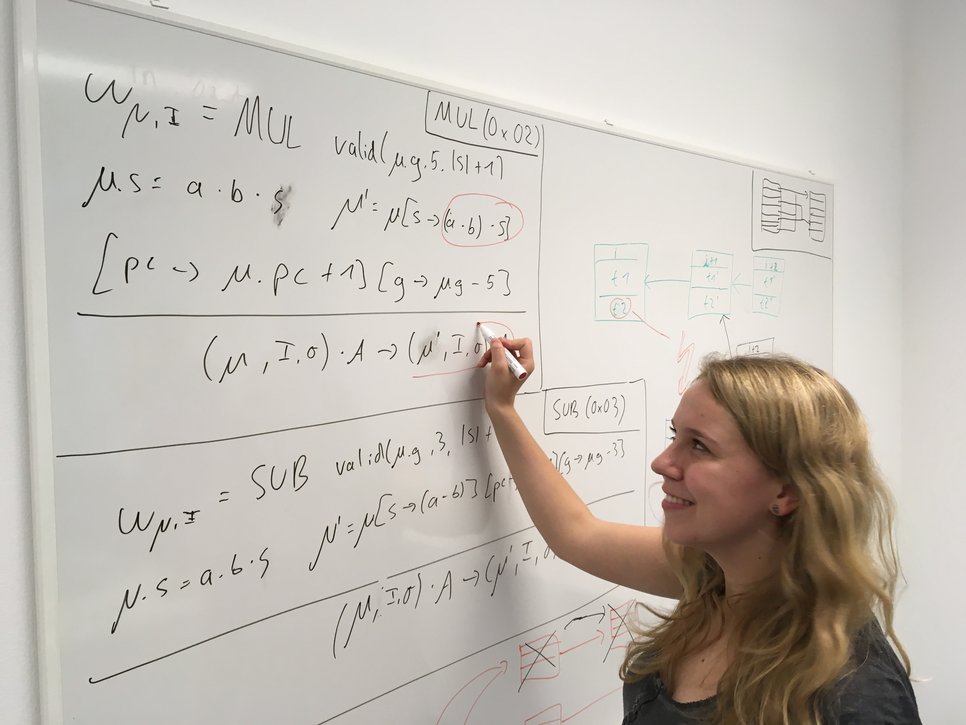

For one thing, new software has to be written for all financial transactions - not only for transfers, but also for other financial products such as investments or loans. And where code is written, errors and thus security vulnerabilities occur - we all know this from off-the-shelf software that we use, for which security updates must constantly close new entries for cyberattacks. "When it comes to cryptocurrencies, the security holes are particularly interesting for attackers because there is a lot of money to steal," says Clara Schneidewind. In blockchains, however, the access points for cybercriminals open up not only because people repeatedly make mistakes, no matter how conscientiously they do their job. The technology also brings with it its own security-related problems that present researchers like Clara Schneidewind and her team with new tasks. One of these is that programs operating on the blockchain can no longer be changed afterwards, i.e. updates are no longer possible.

In 2016, a cybercriminal exploited the special feature of the blockchain of a crowdfunding campaign in which donors could withdraw their money. The attackers not only took their own contribution, but also emptied the entire account. Such thefts are possible in the blockchain not least because its software necessarily works differently than ordinary programs. Applications on the blockchain can initiate transfers and also communicate with other blockchain programs in the process. But because anyone can create their own applications on the blockchain, there is no guarantee that third-party blockchain programs are trustworthy. On the contrary, it can happen that interaction with a foreign program has harmful effects on the execution of one's own code. "That is why it is particularly difficult to protect blockchain programs from attacks," says Clara Schneidewind. "But that's also why it's particularly important." Because the cooperative way of working in the Blockchain creates new loopholes for attackers, and not only for money transfers, but also for other financial products.

What does security mean in the blockchain?

The computer scientist's team is not only concerned with detecting concrete points of attack in blockchain programs, closing them and also proving that the security hole is actually closed as a result. The researchers are also asking fundamental questions, such as what security means for such programs in the first place. The special characteristics of the software, such as its decentralized mode of operation, mean that it must also meet different security requirements than conventional programs: It cannot be hermetically sealed off from outside access.

The same applies to data protection. A key feature of the blockchain is that everyone can check everything. However, those who deposit their money in the blockchain do not normally want to be identifiable by name for everyone. Nevertheless, it must be possible to assign a sum of money to an owner. The blockchain must therefore not manage data completely anonymously. Pseudonyms are the method of choice here. But pseudonyms are cracked from time to time. To prevent all of a person's transactions from being discovered at once, a person is given multiple identities in the blockchain. So often a person transfers money to themselves as it flows from one identity to another. "You have to develop something like this carefully," says Clara Schneidewind. "And we also have to prove that the solutions are secure."

Social relevance motivates the researcher and the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation

In addition to security and data protection, there are other open questions with blockchain technology: a blockchain is always stored on the computers of all users, and all computers must of course also follow all changes in complex computing operations. This requires storage space, computing time and a lot of energy. The blockchain therefore currently only manages seven transactions per second, while the credit card company Visa processes 10,000 transactions in the same time. Clara Schneidewind's group is therefore looking for ways to use the advantages of the Blockchain and mitigate the disadvantages. "Blockchain is like a hammer," says the researcher. "The question is whether we always need it." It is conceivable, for example, that vouchers are issued for monetary transactions that are registered in the blockchain. If such a voucher changes hands, i.e. money is transferred, the blockchain might not necessarily have to store the transaction on every computer involved and for all time.

The increasing importance of cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology in general was a major reason for the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation to support the research of Clara Schneidewind's group. The foundation supports projects in education, especially vocational training and further education in the field of modern technology, in science, especially in information technology, in health promotion and in sport. The Heinz Nixdorf Foundation also already supported the Heinz Nixdorf Centre for Information Management of the Max Planck Society, from which the Max Planck Digital Library emerged. Together with other research institutions worldwide, the latter is now building its own blockchain called Bloxberg, in which researchers can register their results at an early stage without publishing them. In this way, they can later prove that they had already achieved a result at a certain point in time - an important question when it comes to who is to be credited with a discovery.

The social benefit is an important incitement for Clara Schneidewind to dedicate herself to the blockchain and its applications. "In the beginning, I was mainly attracted by the mathematical challenge, but the social relevance has become more and more important as a motivation," says the computer scientist. "I think it's important to explore what technology can do today - for better or for worse. Only then society can make an informed decision on how to use technology."